The missing piece: Operating Systems for web scale Cloud Apps

2013-10-11 08:35:13 +0000

This image shows how the general computing paradigm changed over time.

Source: Cloudscaling Blog

Interestingly enough almost every paradigm came with an operating system platform that fit its needs. Except cloud computing - so far.

This article will explore the current state of how applications are deployed in the cloud and why the current base operating system really is not the right way to go. I will start with the configuration of applications and deployment world how it is done now. I progress to show how it should be, going on to look at the assumptions of operating systems at them moment and how they fit the web scale cloud computing paradigm, closing with some links to interesting projects that actually implement these new ideas of cloud optimised operating systems.

Configuration vs. compiled in behaviour

How does software delivery work in a bigger context?

If you look at the software delivery process from the end user’s perspective it looks like this:

- A new software need is identified.

- Software needs to be “provisioned”. This can mean the software needs to be created (as in programming) or bought, or installed. It doesn’t matter. “The business/user” just cares that it can be used. It should work.

- Software is used

- User uses software and is happy. If not, go back to 1

If you look at the problem from that perspective it really makes no difference what software “creation” vs. “installation” means. In the times of SaaS “installation” from the users perspective might just mean “filling out a web form”.

If you break it down from a supplier perspective the whole process might be called “deliver software” or “provide means for users to acquire software”.

As we will see the difference between “what is software and what is configuration” is also very dependent on how you look at it.

Where does configuration start and software behaviour end?

Configuration is just the last piece of programming outsourced to ops people. It can be done in a good way by explicitly using good programming principles like well defined APIs or in a bad way by just leaving decisions to the deployment guys who then need to figure out the last bit of what is required in terms of behaviour.

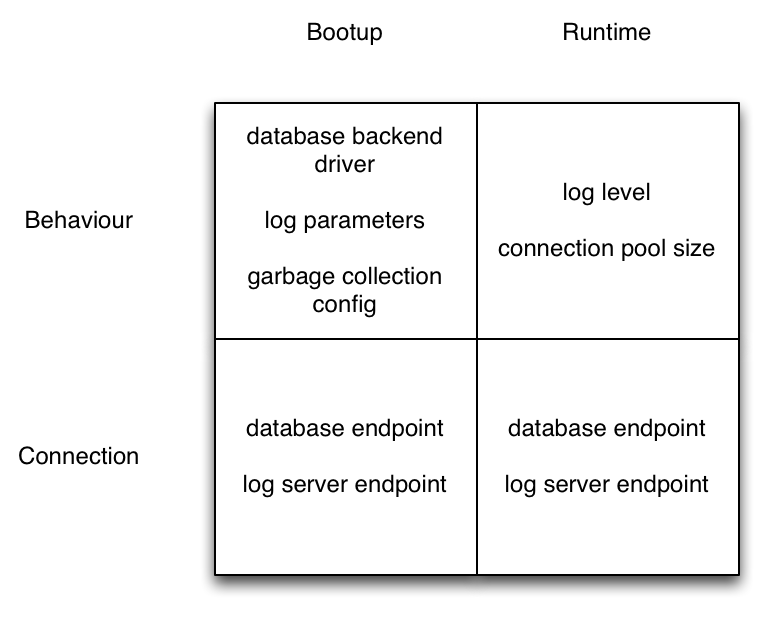

There are two main aspects to configuration (system behaviour and connection to other parts) which each have two values - leaving us with a two-by-two matrix (OMG!):

As you can see, most of the “boot up” config parameters also make sense to tweak at run time. This could be done either by changing config files and restarting the process or directly via API. All of the “boot up”/”behaviour” parts cloud be statically compiled into your application, because you wouldn’t want to change them at run time anyway.

If this is so simple, why does config files exist anyway? The compile statically into your application part just did not make sense in older delivery models. With fast build times and the possibility to bake everything together and re-deploy in seconds or at least minutes, this approach becomes a valid option to explore.

The plethora of Chef cookbooks and Puppet modules and meta cookbooks (in form of blog posts that describe how you create them or use them) shows that there is no clear cut. It’s not entirely clear where a “software package” ends and where “configuration” starts.

And that’s really the point. What if there was no configuration at all?

Deploy a Rails app on Heroku. Do you have to do any configuration? Not really. It just works. You create a web app, deploy. Delivery ended. That’s unfair: Heroku is a Platform-as-a-Service, so THEY just do all configuration so you don’t have to. That’s true but look at database configuration: Heroku just gives you this information via environment variables through a defined interface. An API. Oah!? What? This is software development: APIs!

So configuration itself is just a lazy programmers way of not writing the code in a specific way and letting the admin/ops people to the last step of coding. And configuration management systems like Chef basically now are an IDE for them so to speak.

If you deploy software in one target environment (e.g. only yourself, SaaS-style) you should have only a very small amount of config: staging vs. prod database config, tuning options.

And if you have more than one customer - maybe you should not be lazy and provide configuration options but create different software packages for each customer. Crazy? Well. Either YOU compile your software package or you “outsource” it to your customer. Which option is nicer? And who might be better suited to to that?

What are configuration files? Basically an API that is called once (start of service) to tell the service how to behave. That API is called by Chef, Puppet or your sysadmin. If you think of a software system with an actual API like that you would really think that it’s not good at all. A file-based API? And tomorrow we’ll start using TFTP again and use COBOL to parse the files.

So basically configuration should not exist in the form of config files. There should be an API to the app that can configure it at runtime, e.g. to point it to other services it needs, or to tune it in some way.

Why are we still using mostly 20 year old server operating systems?

What do you need an operating system for? Let’s take Ubuntu or RedHat Linux? It is a nice, stable multi-user unix system. What do you really use that operating system for? Memory Management. Excuse me? You deployed a Java app. So the Java VM does that. User management? Well, who cares about the 50 users on the system, if the only one that matters is www-data running Apache and Tomcat? Process isolation and management? To isolate the Java VM from what exactly?

Multi user

The multi-user part is a piece from the past, that’s still in there because no one has removed it. If you think about the multi-user capabilities in Unix and also Windows based systems and where they come from, it is clear that they are rather useless in web based cloud applications. Basically every VM runs a specific part of the application (e.g. database or web server) and only that. Even the security part mostly does not make sense on the operating system level: If the attacker breaks into the web app, they’ve got the data. No need to be root on the system. The user isolation was not isolating so much useful stuff at all.

Application packaging and delivery

Another point that’s partly related to the config problem mentioned above: How is the software “packaged”? This problem has been solved by Linux distributions a long time a go… for the requirements of long time ago: Scheduled releases with rather static dependencies. If you try to create a distribution package for a modern application that you want to distribute rather rapidly for either downloadable software or distributed via web service with the OS just as the basis, you end up with rather weird constrains on your software. I don’t go into details here. Check out these posts for more detail: Why You Should Stop Fighting Distro Vendors - Part 1 and Stop fighting Distros - Part 2

This problem is so common that most people end up doing the pragmatic thing: Just tar.gz (or fpm) your application plus all dependencies and deliver it via scp (or bittorent as Facebook does) to many servers. Java apps did not care about this at all because the JVM encapsulated everything anyway and you just deployed WARs or JARs with everything they needed in them.

So if you take these requirements and think about how an operating system would look like that satisfies all these and does nothing extra, it wouldn’t look like any Unix-like or Windows-like system at all.

In most cloud environments the base image is a Linux “JeOS” (just enough operating system). This however still has all the concepts and baggage of a standard Linux system and is not optimised for the requirements of large scale cloud app deployments.

The bottom up approach to cloud requirements

All you really need is a Kernel that can execute some kind of platform executable and your application that has access to an TCP/IP stack. Disk Access? Only if the part of the system is stateful (databases). Webservers could get away without it (or with r/o access in the image).

For configuration most of the time you would only need an IP address plus TCP port or URL for some connection to other services (endpoint config). This needs to be managed dynamically because services go down, change IPs etc. - For this part many people use Apache Zookeeper and not a config management tool, because this config might change at moments notice and it’s distribution has to be instant.

Netflix basically use this kind of model, however not in a totally stripped down way. They use a CentOS base image + Java-Stack + Application. Their build and deploy works like this: Bake Full OS-Image + Stack + Current App version with defined config options into AWS image and then deploy the image n times.

This somehow seems to be the way Smalltalk VMs/Images are deployed. There has to be some kind of law that states, that Smalltalk actually was right with its design decisions and every better programming system will eventually implement the Smalltalk ideas ;-)

What does this mean if you think this thought further:

You end up with a warehouse scale computer, whose processes (e.g. VMs) in the operating system (hypervisor, VM-orchestration layer) can be controlled via HTTP REST calls. The processes will communicate via TCP/IP.

The concepts are basically still the same as in an local operating system (message based IPC, processes) only at a higher level (Hosts, VMs talking via REST or MQs).

Interesting Projects that implement this idea

This idea is actually being explored in various projects - sometimes more radical, sometimes not. Here is an overview of the projects I found that go in this direction (Contact me if you know another one!)

Running an application environment directly on a hypervisor:

- OpenMirage - OCaml running on Xen

- HaLVM - Haskell running on Xen

- Oracle JRockit Virtual Edition - Java on Hypervisor

- Erlang on Xen - Erlang on Xen

- Redis on Xen - Redis fork that can run directly on Xen w/o OS

Stripped down operating system approach (either new kernel or Linux based):

- OSv - Kernel + TCP/IP + ZFS to run Java or other app stack

- CoreOS - Stripped down Linux + distributed config management

- Docker - LXC containers + management of containers for app deployment

- SmartOS - Illumos Kernel + Zones (or KVM)

- Returninfinity - Minimum OS kernels for HPC optimized for x86-64bit

- ZeroVM - A cloud hypervisor - somewhere between BareMetalOS and docker

Advantages of the cloud operating system approach

- Security: Isolation is thought of in terms of networks, locally everything is single user. Which is the case for most web apps anyway (www-user) (mysql user)) - Breaking in for Botnet purposes is harder (you own the vm and then what?), reduced attack surface

- Elasticity: e.g Erlang on Xen or Docker spin up new applications in milliseconds instead of seconds or minutes for normal VMs

- Faster: no or less operating system overhead

- Build with configuration distribution in mind: e.g. Core OS has a distributed config system

- App deployment is simplified: The whole image can become the unit of deployment. Basically the kernel now is only a small piece attached to the application rather than the other way around

Disadvantages of the cloud operating system approach

- Monitoring: You cannot use standard monitoring tools, on the other hand you’d probably don’t need them. Just use in App monitoring and metering

- Debugging: Your application has to provide some remote debugging interface, because the layer beneath might not have it (e.g. no ssh)

- Security: The attack surface is minimized but that does not mean everything is solved. You still have to secure your app

- Current System APIs might not be there: Depending on the approach you might not have POSIX-APIs or higher level Linux-APIs for lower level stuff.

Conclusion

Configuration is a very important aspect of cloud based application deployments and there are tools like Puppet or Chef to address these needs. However they still operate on the assumptions that are provided by the way the current Operating systems are structured. A more radical, fundamentally different approach to these problems is provided by new operating system environments that are optimised for the cloud. Most if these systems are still experimental, others seem to be almost ready to use (e.g. CoreOS, Docker).

Related Posts

- Stop writing tutorials - start writing Vagrantfiles or Dockerfiles - Make use of modern tools to make tutorials understandable as well as executable

- There will be no reliable cloud (part 3) - How I stopped worrying and love the cloud

- There will be no reliable cloud (part 2) - Complexity and scale lead to a system design that can only be unreliable at the infrastructure layer