In while the first part was more basic information and technical, the second part will be about why I think it is impossible and not viable business wise to aim for high availability of the cloud in the infrastructure layer. Part 3 will then go into why this actually isn’t that bad an we can still use this “crappy infrastructure” to build systems that are available to the end user.

I just want to make the following point:

Complexity + Scale => Reduced Reliability + Increased Chance of catastrophic failures

This is all this post is about.

Complexity

Almost any software system is a complex system. A software system that has networking components certainly is complex and if you put it on a cloud infrastructure, I think there is no argument that this system is not complex.

Complex systems fail in certain ways. If they are poorly designed these failures are catastrophic, meaning the whole system is taken down. In terms of the cloud this means: All software systems that run on the infrastructure are not available any more and may not recover ever.

This is very abstract, so where does complexity show in a cloud infrastructure?

Failure domains

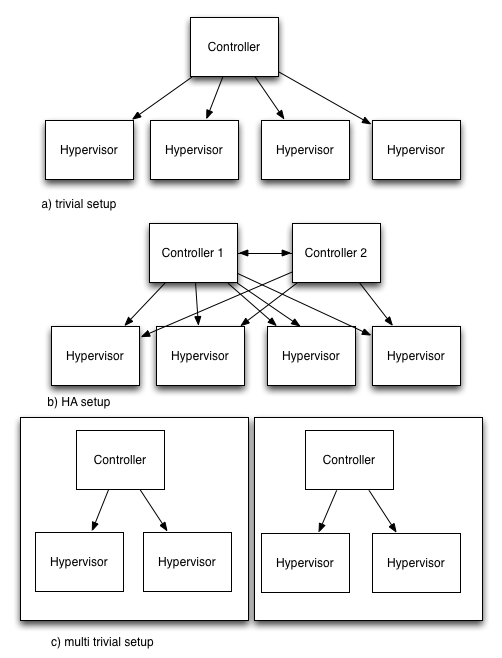

Let’s look at a basic cloud infrastructure setup (say a compute infrastructure implemented with OpenStack nova):

We have a controller and four compute nodes (Hypervisors). Now the controller is certainly a Single point of failure, so let’s add another one (HA!). You can immediately see how this increased the complexity! And if the failover fails you gained nothing.

Compare that with the approach of - instead of adding another HA-style controller - creating another zone which itself is as simple (and unreliable) as the basic example.

If you just look at one zone it is unreliable and does not seem to make sense. But if you look at the whole system consisting of two zones you can actually see that you gained something: You have two independent(!) systems with known failure semantics: Failure of one controller in zone 1 will never lead to a failure of zone 2.

Of course you have to build your system in a way to make use of this. This is topic of part 3.

Why is this approach useful? Remember: Almost any public cloud provider takes this approach. And please don’t start to argue that one controller per zone is not a good idea and you still need HA for that. This is a pattern. Of course you should make the controller in a zone as reliable as possible - taking into account the trade-offs of zone failure and costs.

At the controller level you can actually make that piece of the infrastructure more reliable with very small costs. In the OpenStack case: Just add a MySQL galera cluster, UCARP virtual IP in front and you’re basically done. 1 changed component and 1 additional component is a small price to pay for the gain.

The main idea here is about the “failure domain” pattern which splits and reduces complexity instead of increasing it using dependent systems like HA-pairs.

Some math - or not

Ever since statistics class in school, I’ve had the gut feeling that using probabilities in the real world is somehow wrong. I was thrilled to read my feeling was right. There is actually a good video about the whole topic by Michael Nygard Reliablity engineering matters except when it doesn’t. Please watch the whole thing or don’t watch it at all. If you stop half way, you’ll get everything wrong.

“It is often the failover mechanisms themselves that generate the failure” - Michael Nygard @ 20:20 in “Reliablity engineering matters except when it doesn’t”

The basic heuristic for reliability of systems is:

The higher the number of dependent components => the lower the overall availability and the bigger the impact of failure

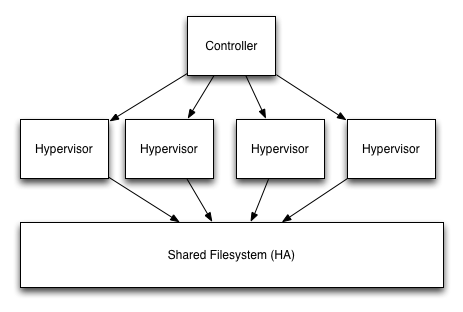

And this is not a linear dependency. As soon as you introduce a dependency like a central service of any kind (think network filesystem, SAN, the network itself) you add a dependency.

So if you consider this and now think of a cloud system that uses say 1000 compute nodes which, for normal operation, could be rather independent. Then you add some crazy HA-failover logic to your cloud management software that is supposed to fail over VMs via live migration from any node to any node. Well, congratulations, you just decreased the reliability of your overall system and increased the risk and impact of failure (total system failure!) by orders of magnitude because you just tied all compute nodes to each other.

An example that shows up again and again are failures of AWS EBS as a common source of AWS AZ failure, like the one around christmas last year. The Elastic LB had a dependency on EBS. EBS fails. Now the whole region is down.

I actually did not provide any calculation here - because I think you can only miscalculate here and come to the conclusion that “it’s actually not that bad”. It is important to get the connections and implications between dependencies, complexity and how scale increases the impact and likelihood of failure (even if you cannot say by how much).

Another thing to consider when using the math-toolkit: Most of the reliability calculations that are used, come from mechanical engineering where things actually behave in a somewhat predictable manner. When you’re dealing with just bare metal servers this may apply. If you add virtualisation you now have software added to the stack. And software failure characteristics are very different from hardware.

Also complexity and non-independent system change the calculations drastically - and you still have to predict probabilities. System failures are no dice rolls!

If you’re interested in the math (and where it works and where it doesn’t), watch the video mentioned above and read this paper if you think you can somehow predict stuff in a real, complex system.

Problems with failures in big complex systems

Another problem with complexity + scale is the type of failures you get. Most of the failures start local and small but then turn into cascading failures like this Google App Engine failure.

There are many ways this can happen and a few ways you can protect against this - some of which are shown in Release It!.

The general approach here is: make failure as local as possible and if something starts to go wrong, make it fail hard and small and contain the failure. Again: Defined small, failure domains and independent systems.

If you have a lot of dependencies in the infrastructure you’re not only increasing the likelihood of failure but also make recovery harder. The Thundering herd problem comes to mind.AWS EBS has been hit by this more than once.

The importance of partial failure

Even though the system design that is communicated to the outside is “expect one complete cloud zone failure” it is important to design the system so that it can actually fail partially and work in a degraded mode. So to have small failure domains (e.g. compute nodes) that fail in a predictable manner (e.g completely and only in hardware) helps with that. So a degraded operation might be: 20 of 100 nodes failed but the other 80 are fine and don’t care about the failure.

One of my favourite examples of partial failure/degraded operation is the Airbus flight control software with its different flight control laws. A lot of stuff can fail and the plane is still maneuverable. As far as I know nobody ever died from a failure of this system.

You have to design for failure anyway

There’s a great post about UDP clouds vs. TCP clouds clouds. I like the analogy. I disagree with Massimo’s conclusion: He puts it as if with TCP you’d never really expect a “connection reset” or anything like that because TCP is reliable. The truth is: You have to design for failure anyway! It does not matter how reliable your underlying infrastructure is. And you can actually implement some very performant and reliable applications on top of UDP… ask some of the IT guys at Wall Street.

Business side of things

There are also costs to provide reliability at cloud scale. One of the best papers on this topic certainly is The Datacenter as a Computer: An Introduction to the Design of Warehouse-Scale Machines. It basically comes to the conclusion that Software reliability is cheaper than hardware reliability at scale because the additional costs of a software deployment are basically zero.

One thing to consider here is also this scenario: Most web scale systems consist of a large stateless part and a small stateful part. The stateless part is easily scalable via scale out and a single component does not have to be reliable. Using this setup, it does not make sense to host the stateless part of the system on a highly reliable cloud system (if we pretend that it exists). You don’t want to cast pearls before swine, do you?

The main idea of a compute cloud is to be a general purpose compute environment. To make it as flexible and cheap as possible for customers to use, it does not make sense to provide a super reliable infrastructure.

Now what?

I hopefully showed why a single compute node or zone of the cloud will never be reliable. This “reliable cloud” problem really only exists if you think about compute instances in the cloud of “physical servers”. They really aren’t servers. So the real question really becomes: WHAT does have to be reliable and does it have to be a certain part of the infrastructure? Everybody seems to have accepted that hard disks will fail all the time and we find ways to design around it. I think the same is true for “the server” in a cloud setting or better “the cloud compute instance”.

So if we accept this reality and move on, it turns out we can actually build reliable applications on top of such infrastructure. Mission critical apps in the cloud? Well, NASA does it and they don’t seem to use their rocket scientists to solve that problem.

More in part 3.

Related Posts

- Stop writing tutorials - start writing Vagrantfiles or Dockerfiles - Make use of modern tools to make tutorials understandable as well as executable

- The missing piece: Operating Systems for web scale Cloud Apps - Operating systems that are optimised for cloud applications regarding configuration support and the distributed nature of apps are not there yet.

- There will be no reliable cloud (part 3) - How I stopped worrying and love the cloud